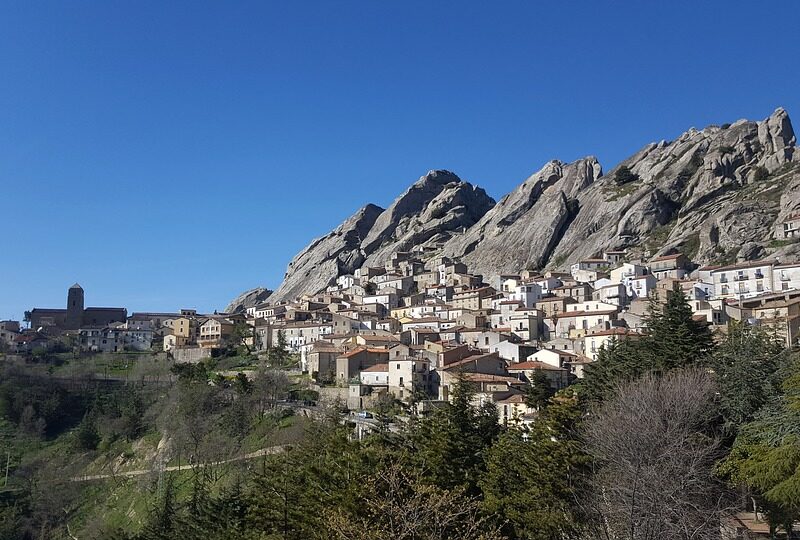

The Borgo of Venafro

For centuries, the mountains around Venafro have tirelessly protected the borgo and its surrounding plain, delicately painted in infinite shades of green.

The origins of this borgo are interwoven between mythological Greek legends and the history of the ancient Samnite people, who were native to this continent. In the ancient lanes of the historical center, every stone has a story to tell. Following the “Via per Mezzo”, the central street, you will find ancient Medieval workshops, set between newly restored houses and the ruins of a Roman colony. The Pandone Castle fondly observes this enchanting borgo, closed in a world of its own, a refuge for modern exiles in search of peace and tranquility.

The historical center of Venafro bears witness to the miracle of life reborn every day, as waterfalls and imposing rivers flow from its lake ‘la Pescara’. Following their course, the waterways leave the houses of the town behind them to flow through the surrounding green and silver olive groves, Venafro’s natural treasure chest, providing world-class, premium olive oil every year.

Whoever comes to Venafro easily forgets their quick touristic pace and is captured by the delicate charm of this fortified borgo, a timeless place to be savored slowly, one discovery at a time.

History

‘You, mortal! Do not attempt to challenge the Gods!’ was Apollo’s warning to Diomedes, an Achaean warrior, who, during the Trojan Wars was trying to kill Aeneas, and wounded his mother, the goddess Aphrodite instead, inciting her wrath. Homer describes Diomedes as a fierce warrior gifted with the loyalty and astute judgment of a diplomat. Legend has it that after the fall of Troy, and more misadventures at sea, Diomedes landed on the Italian coast, where he abandoned his war-like fury to promote civilization and culture, founding various cities, among them Venafrum, today known as Venafro.

The grandeur of Homer’s Greek epic lends the fascination of legend to Venafro’s origins, but historically speaking, the foundation of the city is attributed to the Samnites, an ancient tribe of Italic origins. The plain of Venafro has been inhabited since prehistoric times, and during the Social Wars between the Samnites and Rome, it was repeatedly conquered and destroyed, first by Mario Egnazio and then by Silla.

The first written sources attesting the existence of Venafrum date back to 300 BC when the borgo was under the Roman jurisdiction of Massimiliano, becoming a Roman colony in 14 BC, during the reign of Augustus. During this period, an aqueduct was constructed and Venafro’s city plan was given a Roman imprint, traces of which can still be seen today. Many Latin authors have sung the borgo’s praises, describing Venafrum as a peaceful, friendly place. One of the first to appreciate the town was the poet Orazio, who described it has a holiday resort. Plinio the Elder and Marziale also championed it, while Licinio is even credited with introducing the production of olive oil to Venafro, bringing immense economic fortune to the town.

From 774 to 787 AD, the Venafro plain was the setting for battles between Charlemagne and the Lombard army. And while it has usually been peaceful, the borgo has gone through other dark moments, in particular during the Middle Ages, when two earthquakes, one in 1349 and another in 1456, seriously damaged the borgo, which was already weakened by pestilence and poverty.

Leaving this sad period behind, Venafro began to develop again, thanks to interventions of urban expansion: prestigious palaces and numerous churches were built, leading the borgo to be called ‘The City of Thirty-three Churches’.

On the wall of the Cimorelli Palace, a marble plaque commemorates one of Venafro’s most important events: King Vittorio Emanuele di Savoia was a guest here before heading off to Teano, where he would meet Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Until 1863, Venafro was included in what was called the “Land of Labor”, which was the agricultural part of the county of Caserta, in the region of Campania. This is probably why, still today, the city has a great cultural and linguistic affinity with that region. After 1863, the borgo was annexed to the Province of Campobasso, in the region of Molise.

In the period after the Unification of Italy (1861), the borgo was characterized by rebellious activity against the Royalists called “brigantismo”, which caused the General Ferdinando Augusto Pinelli to cancel Venafro from all the maps of the area.

In 1911, Venafro had become peaceful again, so much so, that during a grave illness, the beloved Apulian saint, Padre Pio, was sent there by his Neapolitan doctor for a period of rest. It was during his stay in Venafro that he began to manifest the first divine and diabolical apparitions and supernatural phenomenon that would lead the young priest on the path to sainthood.

During the dark years of the Second World War, Venafro was not spared. Between 1943 and 1944 it was the theater of war for violent clashes between the Germans and the Allies. It was the Allies who bombed Venafro in 1944, confusing it with the town of Montecassino, causing the deaths of four hundred civilians and military personnel. In 2005, in memory of this tragedy, the President of the Republic, Carlo Azelio Ciampi, awarded Venafro with the Civil Medal of Valor.

In 1970, Venafro passed to the province of Isernia, and in 1994 it became a member of the A.N.C.O., the National Association of Cities of Oil, a consortium of olive oil producers, carrying on an agricultural tradition that has been honored in Venafro since its origins.

Ceppagna

A crown of olive branches surrounds Ceppagna, a simple and authentic hamlet nestled in the nearby hills. Even though Ceppagna has little more than six hundred inhabitants, its history is extremely ancient, beginning with the Samnite population more than 2,500 years ago. The name ‘Ceppagna’ is derived from cippus, the name of an ancient star during the time of the Roman Empire, which marked the distance of the location from Rome.

The historical center of Ceppagna is small and delightful, built around the church of Madonna del Rosario, where the festival of the patron saint is celebrated on the first of October every year.

Vallecupa

With one hundred and twenty inhabitants, nestled in a tiny valley protected by the rocky slopes of Monte Cesina, Vallecupa is Venafro’s second hamlet. The refreshing sea breeze caresses this tiny borgo overlooking the blue expanse of the sea, just over three hundred meters from the town. The historical center is graced by the little church of Santa Maria degli Angeli.

Le Noci

The smallest of Venafro’s hamlets is Le Noci, a tiny borgo inhabited by a family of shepherds. It is located around four hundred meters above sea level on the slopes of Monte Sambucaro and is always pleasantly cool, thanks to a light and refreshing mountain breeze.

Pandone Castle and The National Museum of Molise

The Castello Pandone watches over the borgo of Venafro from the slopes of Monte Santa Croce, continuing to protect the village as it has done since it was first constructed.

The castle was built over the ruins of a defensive structure dating back to the third century BC, and a successive Roman fortress. Today, the oldest remaining part of the construction is a square tower from the Lombard period, built in the tenth century.

The castle has undergone numerous modifications and enlargements over the centuries. The first interventions were in 1349, during the Angevin period, which included the addition of circular towers, hidden walkways for soldiers, a moat and two drawbridges.

In 1443, Alfonso d’Aragon consigned the county of Venafro to Francesco Pandone, who also took possession of the castle. At his death, the fief and its castle passed into the hands of his son Enrico, who gradually softened the austere character of the fortress, transforming it into an elegant noble residence. Enrico Pandone loved art and horses, and by combining his two passions, graced the castle with a unique decorative theme. Walking through the rooms of the castle you can admire portraits of the most beautiful specimens in Enrico Pandone’s stable. The paintings of the horses are life-size, painted with a technique called stiacciato: a layer of plaster is laid out, creating a low-relief figure on which color is added. Next to each horse, a descriptive plaque reports the name, age, race, and color of the mane, as well as an ‘H’ symbol of the ‘Henricus Stables’. The paintings were created by artists versed in the Spanish and Catalan style, who worked in a studio of the Neapolitan school.

In the castle, you can still admire the noble quarters of the first floor, a salon from the 1300’s, and a magnificent garden, where, for the entertainment the castle’s guests, a little theatre was built, with a false, fixed curtain, for performances of theatrical comedies and dramas.

The Pandone dynasty were not the only ones to inhabit the castle, and throughout the rooms there are the family crests of everyone who lived there after them: in the entry hall there is the coat-of- arms of the Lannoy family, surrounded by other smaller coats-of-arms representing the noble families to whom they were related, The Pandone family crest is in the Ballroom on the main floor, with the crest of the Perretti-Sovelli family placed above it.

Today, the castle is the site of the National Museum of Molise, which for years has worked in service to the community, carrying out long-term research. The principal objective of the museum is to protect and share the artistic wealth of Molise, and also to create an artistic dialogue with other regions by exhibiting their artists as well: the museum exhibits pieces from the Museum of Capodimonte, the National Galleries of Ancient Art in Rome, and the Palazzo Reale of Caserta. The works on exhibition in the museum span a historical period starting from the beginning of the Middle Ages in 500AD, up until the 1600’s, featuring paintings and decorations that embellish the rooms of the castle with over one thousand years of art.

Concattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta

In the fifth century AD, Venafro became an Episcopal seat and the first Cathedral was built. The original early Christian church that once existed is no longer recognizable today: over the centuries, natural calamities and Barbarian invasions continually damaged the structure, necessitating restorations and changes.

The original church was quite small and overlooked the Roman forum from the hill of San Leonardo.

In the eleventh century, the Episcopal seat of Venafro was joined with that of Isernia, and the Bishop Pietro da Ravenna began work on the renovation of the façade. He also replaced the single nave floor plan to three naves and had chapels built along the walls. A triumphal arch was constructed and the façade was embellished with symbols taken from Medieval bestiaries.

Two earthquakes in 1349 and 1356 seriously damaged the entire structure of the church, requiring new restoration interventions, during which Gothic elements were introduced, above all to the façade.

In 1935, further restoration brought to light some marvelous frescos dating back to the 1400’s.

Today, the Concattedrale of Venafro appears in the Gothic architectural style, with no particular decorative elements on the facade. There are three entrance portals with round arches and a bell tower. The interior conserves simple lines, with the naves divided by two lateral arches.

Venafrum. The Ancient Roman City

The Venafro plain has been inhabited since antiquity, as attested by the ancient Samnite temple dating back to the fourth century BC.

In the third century BC, Venafro became part of the Roman Empire and began a flourishing period of development that culminated in 14 BC, when the borgo became a Roman colony under Augustus. During this time there was a complete overhaul of the urban plan and many public and private buildings were constructed. The newly enhanced colony of Venafro became one of the most important in the area, thanks in part to the production and commerce of premium quality olive oil. Unfortunately, in 346 AD a violent earthquake devastated the plain, and the inhabitants of Venafrum abandoned their town to found a new borgo in the hills to the west.

Today, much of what was ancient Venafrum is protected inside the Archeological Park.

The ancient Roman city walls, most of which are still standing, surround some of the most important private and public buildings constructed during the Roman Empire of Augustus. The walls were probably built in 40 BC, by decree of the magistrate C. Aclutius Gallus, as indicated by the epigraph inscribed on the walls.

The theater was constructed in the hills of Monte Santa Croce, built in different historical phases. The original nucleus included only the ima and the media cavea, or seating area, to which the summa cavea was added at a later date, with the function of containing the landslide-prone terrain of the mountain.

The ninfeo dates back to the second century AD, together with the hydraulic systems on the sides for water displays in the orchestra area.

An earthquake that hit the area in 346 AD caused some of the sculptures in the theater to collapse, and so they were stored in the ninfeo with the intention of restoring them at a later date.

Historical evidence indicates that by the fifth century AD, the theater was being used as a shelter and for civil habitations.

A short distance away, we find the Amphitheater Verlasce, built in the first century AD. It has been preserved until the present day thanks to a unique urban intervention in the 1600’s, which constructed buildings in a full circle around the theater, creating a large, perfectly round piazza completely protected by the houses around it. The amphitheater was commissioned by a member of the gens Vibia, an important family of the Roman nobility in Venafro, as cited by an epigraph found at the entrance to the theater.

Among the noteworthy private buildings built in the Roman period is a home in via Licinio, with marble and mosaic flooring and decorative terracotta depictions of griffins. Analyses of the various rooms and flooring, some in mosaic and some in “Coccio pesto”, a particularly hard type of terracotta, revealed that the structure had three phases of life: the most ancient, identified by the use of tuff stone blocks, one dating back to the third century AD, a later era in which some areas of the flooring were raised. Unfortunately, during the Medieval period the building was used as a quarry, with material being taken to build other homes, which greatly compromised the structure’s architectural integrity.

Another important building dating back to the period of Imperial Rome is the aqueduct, which was constructed between 17 and 11 BC. Its use was regulated by an edict, which exists to this day. The entire structure was thirty kilometers long, partly underground and part built with structures made with opera cementizia. It started from the mouth of the Volturno river and reached the highest part of the city, where the Castellum Acquae, or reservoir, was located.

Along the Roman roads that led from Venafrum to Cassino, Teano and Isernia, the necropolis are located. Of further historical interest is the existence of isolated funeral monuments, away from the group burial sites, indicating the inhabitants’ custom of building private tombs on their own land.

No Roman municipality could exist without a temple and a sacred area, and the most important temple in Venafrum was dedicated to Magna Mater, the Great Mother, but unfortunately it has never been located. According to one hypothesis, the temple once stood in the same place as the current Cappella di Monte Vergine. Here, in fact, a terrace constructed with opera cementizia was found, which probably supported a public building, almost certainly a temple. This premise is reinforced by evidence of the worship of a female deity in the surrounding sacred area.

Poised between the ancient past and the ephemeral present, Venafrum invites you to relive its glorious days by exploring the ruins of the ancient Roman city, a place of unique magic, which has courageously resisted the impetuous flow of time and the numerous calamities that have struck the area.

The Olive Grove Regional Park of Venafro

In 2008, the ‘Parco Regionale Agricolo Storico dell’Olivo di Venafro’ was established. The territory of Venafro is famous for the cultivation of ancient olive trees, trees with roots going back to the times of ancient Rome, when the olive oil produced here was known as “the best in the world”.

The Latin scholar, Cato, in his work De Agri cultura, promoted the cultivation methods used in Venafro as a standard of excellence to be adopted by all. And he is not the only one to applaud the loving care the community of Venafrum lavished on the cultivation of olives and the production of olive oil.

After a long period of neglect, Molise established this park, in operation for some years now, founded to guarantee a form of protection for its invaluable natural heritage. The ‘Parco dell’Olivo’ is also a symbol of social redemption, transforming a neglected area once left to vandalism.

The ‘Parco dell’Olivo’ begins behind the Concattedrale of Venafro and continues up the slope of Monte Croce, interweaving with dirt trails and the ancient ruins of Venafrum, including a part of the Roman aqueduct and the church of Madonna della Libera.

The citizens of Venafro are the custodians of this park, skillfully cultivating the olive trees to produce olive oil of excellent quality, and who also come to the park for walks and picnics in the beauty of nature.

The WWF Oasis ‘Le Mortine’

A short stretch of the Volturno river marks the border between the regions of Molise and Campania: a corner of the world enclosing one of the most beautiful green areas in Molise.

The ‘Le Mortine’ Oasis was established in 1999, and contains one hundred and twenty-five hectares of unspoiled nature. Following the forest trails you can immerse yourself in the lush green woods, until you reach the river bank and a small body of water: an artificial lake that often hosts various species of ducks. This WWF Oasis is located on bird migration routes, and they often stop and stay for some time. Rare species such as the ‘Moretta Tabaccata’ and the ‘Fistione Turco’ have been spotted here.

The flora of the oasis is varied, passing from various species of Willow to White Poplar. One area is entirely characterized by Black Ontone, interspersed with bushes of Sanguinello, Nocciolo e Luppolo.

The Oasis is truly a paradise of peace and quiet, immersed in the purity of nature.

The Forty Days of Padre Pio in Venafro

In 1910, at the age of twenty-three, an ardently spiritual young man from Pietralcina fulfilled the dream of a lifetime by taking the vows of priesthood, taking on the name that the entire world would come to know him by: Padre Pio.

A year later, at the end of 1911, the young priest was gravely ill, and his superior, Padre Provinciale Francescano, convinced him to go to Naples to visit a skilled physician, Dottor Cardelli. After examining him, the doctor was extremely concerned, declaring Padre Pio’s condition so serious that he only had a few days left to live. He suggested that the dying man be taken to the convent of San Nicandro in Venafro, which was not only the closest, but also famous for the health-giving properties of its climate.

Instead of dying, Padre Pio began a new chapter of his life in Venafro, which from then on would be an existence of miracles, pain and compassion on a literally biblical scale.

Padre Pio stayed in Venafro for forty days, which is often associated with the forty days Jesus Christ spent in the desert. Like Jesus, Padre Pio fasted for long periods, eating only the Eucharist used in Holy Mass. He had visions of the Devil, who tempted him as a nude woman and as various saints, and he fell into states of ecstasy, during which he spoke directly with God.

During this period, Padre Pio’s confessor took detailed notes of what the dying priest said during his ecstatic states, thanks to which we can read the saints’ request to Jesus, asking to experience in his own flesh the pain of Christ’s ‘Passion’ and death. In fact, Padre Pio ardently desired to feel the pain of the nails of Christ’s crucifixion in his own hands.

Various physicians were called to care for Padre Pio during his ecstasies. On these occasions, discordant cardiac activity was registered, as if his heart was going to explode. Still today, there is no medical explanation for this phenomena.

It was planned that young priest would remain in the convent until his death, and so one night the Father Superior began writing the eulogy for Padre Pio’s funeral. As he was intent on finding the right words, Padre Pio himself came to his room, telling him that Jesus had sent him to thank him for the fine words he was using, but also to let him know that it would be a long time before they would be needed, and that Father Superior would not be the one reading them.

At that time, even though he had been an ordained priest for over a year, Padre Pio’s health conditions had prevented him from ever celebrating Holy Mass. His desire to do so was so strong that in his conversations with the Lord, he often asked for the opportunity of being able to hold Mass, beseeching God not to not listen to what his superiors in the clergy were saying about him.

One day, seeing that the priest’s condition was not improving, the Father Superior of San Nicandro decided to write to the Father General to ask about the possibility of Padre Pio returning to Pietralcina, which he had been insistently asking to do. Permission was granted, and Padre Pio returned to his convent in Pietralcina on December 7, 1911.

The next day, he was on his feet celebrating Mass for the first time, to a community that would grow in faith, determination and love during the long and miraculous life of this authentic modern day saint.

Many long and eventful years later, Padre Pio returned to his Holy Father, on September 23, 1968.

Venafro… The city of Taralli

The inhabitants of Venafro will hopefully forgive us if we ‘Italianize’ one of the culinary delights of this borgo in Molise. In Italian, ‘Taralli’ are crisp, fragrant, wrapped flour savories, which in Venafro are called ‘v’scuott’. To make them, prepare the dough by combining flour, artisanal extra virgin olive oil (strictly local!), salt and wild fennel. The dough is worked and then cut into small pieces, worked again, rolled up and then twisted. Once they are shaped, the ‘v’scuott’ are lightly boiled then baked.

The‘v’scuott’ are also the main ingredient in Vanafro’s most famous traditional dish: the ‘Boccone da Re’ (the Snack of Kings). The cuisine of Molise is based on the fresh produce of the local farms: sun ripened vegetables bursting with flavor, mouth-wateringly fresh cheeses and tasty cured meats.

The ‘Boccone da Re’ is prepared by breaking up a fragrant handful of ‘v’scuott’ immersing them in a fresh tomato salad, seasoned with olive oil and salt, and a splash of water. Leave everything to settle for just a few minutes, to soak the ‘v’scuott, and now, your ‘Boccone da Re’ is ready to be enjoyed and savored, an explosion of flavor in every generous spoonful.

_______________________________

Do you known other typical recipes related to this borgo? Contact us!

Italiano

Italiano

Deutsch

Deutsch